Topic: Fixing and testing a KIM-1 video board

Date: 2023 APR 05

Dave Plummer purchased a very complete KIM-1 system with expansion chassis and has been going through it. One of the boards included in the setup was a MTU “Visable Memory” (sic), which is a bitmapped video board. The Visable Memory uses 8K x 8 of dynamic RAM, dual-ported to sit directly in the 6502 address space. The video interface reads the contents of the DRAM and displays it bit-for-bit on the screen. Contrast this to how many video boards of the era worked, displaying either text only, or using a graphics “font” to handle non-text output.

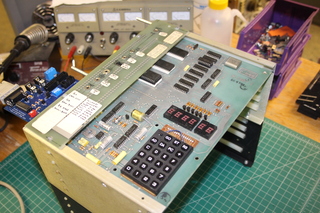

Above is a picture of the repaired Visable Memory board, from the front. The horizontal dimension in the picture is the same as the height of the KIM-1, and the 22/44 connector lines up with the KIM-1’s expansion connector. The vertical dimension is smaller than the width of a KIM-1, but its layout allows it to plug into MTU’s KIM-1 card cage and backplane:

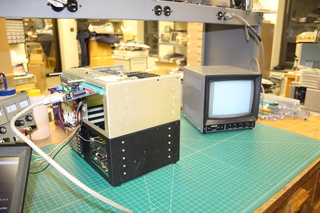

The KIM-1 pictured is my own, but the two MTU card cages and their associated backplanes belong to Dave. The Visable Memory can be used without a card cage, but requires wiring two 22/44 connectors together, and limits further expansion of the KIM-1, so having the card cages was very handy for repair work. Here’s a picture of my KIM-1, the repair of which probably needs its own writeup:

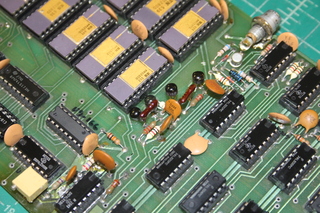

The majority of the Visable Memory board is occupied by a bank of dynamic RAM. It contains 8K x 8 in sixteen National Semiconductor MM5280 DRAMs. Despite being dynamic, there’s not a lot of space dedicated to refresh, as the Visable Memory uses video rescan to perform refresh. Rescan is handled during the PHI2 low time, so it’s transparent to the KIM-1’s 6502 and does not require wait states. A pretty clever design! Due to the power efficiency and low cost of the board, the manual suggests potentially using it as just system memory and ignoring the video circuit.

Another clever feature was the inclusion of a charge pump to generate the negative voltage required on the board: the Visable Memory requires only positive rails, like the KIM-1 to which it attaches.

Repairing the Visable Memory

Dave’s boards had experienced an unfortunate accident: the backplane power supply wiring was mixed up, and unregulated DC power was put on the +5V and +12V rails. This damaged many components on the board, some of which failed outright, and some of which became intermittent or unreliable. Dave replaced the chips that tested obviously bad, but a few others were found in the course of debugging.

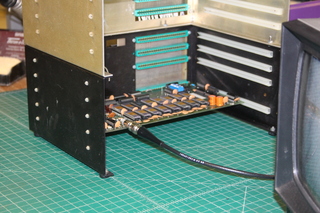

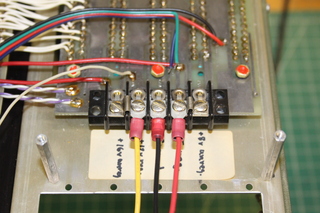

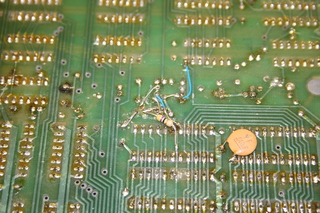

Our agreed-on permanent solution to the problem was to run all boards on regulated +5V and +12V power. This was accomplished by bridging the regulators on the Visable Memory (a modification suggested in the manual) and installing removable bridge clips on the backplane barrier strip:

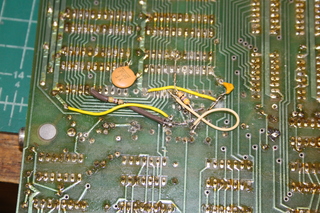

System power during testing was provided from the Lambda LPT-7202-FM bench supply. With power sorted out, and the obvious logic problems repaired, it was time to dig into the transistor level shifters used to drive the chip selects of the DRAMs. The original work was not in good shape when Dave acquired the board:

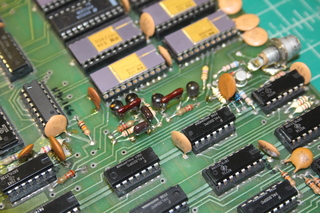

There were burned and lifted traces, pulled through-hole plating, and undocumented modifications. Dave had said he believed one column of DRAMs was functioning correctly (they’re odd/even byte interleaved), but this turned out to be measurement error. Out of four transistors, three were dead. Dave had provided spares for one type, but not the other, so a replacement in TO-106 package was chosen and resistor values adjusted to obtain the required level-shifted drive waveforms. Here’s a closeup of the repaired level shifting circuitry:

There was some additional general clean-up work performed, and a few crusty sockets were replaced out of an abundance of caution. With these repairs, the Visable Memory was basically operational and ready for more involved testing!

6502 Memory Tests

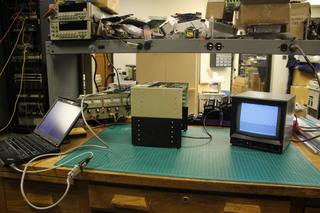

With the repair work done, exhaustive testing of the Visable Memory could begin. The workbench got cleaned up for this, with my KIM-1 and the Visable Memory in the MTU backplane/card cage setup, and a small Ikegami black and white monitor for video output:

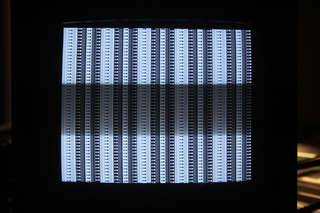

The Visable Memory now reliably produced a static pattern on reset:

Bytes could now be entered from the KIM-1 using either the keypad or serial console and the values would actually stick!

My usual go-to memory test on the 6502 has been the test published in the Ohio Scientific Small Systems Journal, Volume 1, Number 3 (September 1977). This test had proven useful when designing an Ohio Scientific RAM board and has been modified for use on several other systems, including our AIM-65 diagnostic ROM.

I began testing by using the OSI test’s fill function, and blanking the display. It was pretty obvious that there was at least one failed DRAM in the board, as poking values into memory would cause other pixels to switch state. Disturbingly, running the OSI memory test yielded no failures! Many passes could complete without any error.

I dug into the problem and came to the realization I’d hit a pathological case in the OSI memory test completely by chance. I had a failure on a 256-byte boundary, and due to the way the OSI test generates its test pattern, and the fact that the tested area was an integral number of 256-byte pages, the test was completely fine with the write to one address affecting another as long as it was 256 bytes away.

To solve this problem, I decided to port Martin Eberhard’s excellent MTEST4 for the Altair 680, documented about halfway down, here. It’s not 100% functionally identical as the 6502 and 6800 are different in a number of ways, but it follows Martin’s basic prime length walking bit pattern. This pattern flips a lot of bits, and its length helps avoid aligned faults like the one I was catching. It’s also small enough to fit in the KIM-1’s 1K of base RAM. That porting effort is available on Github, though at the time of writing it is not very polished.

Observing the Memory Test

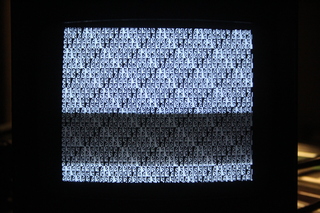

An interesting aspect of testing video memory is that one can actually observe the test patterns in real time. Comparing the OSI test to the ported MTEST4 provides some interesting insight. Here’s the OSI test mid-run:

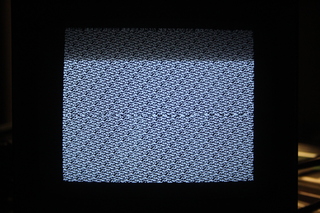

Notice the obvious repeating patterns? This is a function of the sequence generation that the OSI test uses. It clearly works in a lot of situations, as this test has been used by countless hobbyists, myself included, to track down memory issues on OSI systems. Here’s a look at a MTEST4 run:

The update boundary is about mid-way down the display. While there’s clearly a bit of repeating pattern, this image looks a lot more like static on a TV tuned to a dead channel. That’s often a pretty good sign that the randomness is pretty high. Martin’s test is also significantly faster than the OSI test, completing all of its passes in a fraction of the time. More importantly, it reliably and consistently found the dead DRAM very quickly.

The difference between the two memory tests is far more striking when seen in a video, so I recorded them. Sorry for the lousy audio, my tie clip microphone was apparently failing:

Return to Dave

Once we were sure that the Visable Memory board was squared away, it and the card cage were packed up and returned to Dave. He’s since recorded a video and uploaded it to his YouTube channel:

This was an interesting dig for me into a board I’d never worked with before! In general, I don’t have a lot of interest in video boards on vintage computers; however, this one did provide some pretty unique opportunities since it’s bitmapped. I will likely work on a reproduction, or at least modernized workalike, of the MTU Visable Memory in the not-too-distant future!

stuck pixels